A few days ago Anthropic showed off its Claude AI bot using a computer on its own – able to see the screen, identify software, scroll windows, find and manipulate information.

It seems to be a good opportunity to consider what it means for human workers in the long run, since most office jobs are revolving around using a computer.

Admittedly, Claude is still very basic and clunky, but objectively it's only a matter of time – and not much of it – before AI masters using computers, at first matching and then rapidly outpacing us at it.

Humans are just not designed to use PCs efficiently enough – something that Elon Musk observed long before AI tools made their way into our homes and offices.

The solution he proposes is building a digital link between the brain and the machines to transfer our thoughts with a much higher bandwidth that our fingers permit by using a keyboard or a touchscreen.

But there seems to be another, much simpler possibility – that we are going to stop using computers altogether.

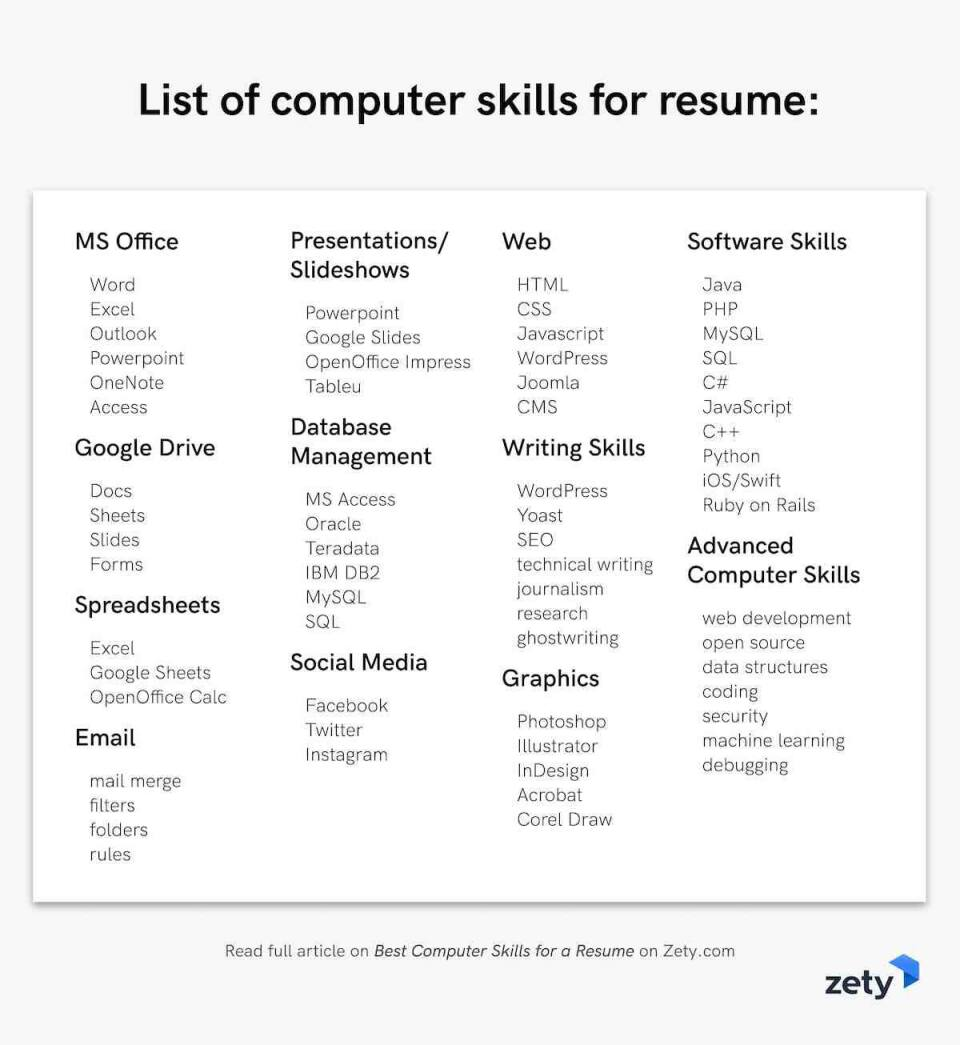

When you apply for any intellectual job today, your CV usually lists software applications you can competently use – from the staple of Microsoft Office, through design programs like Adobe suite, to highly specialised engineering, 3D modelling or industrial programs, depending on the job.

Realistically, we can only achieve advanced competences in just a handful of these – and most of us will never achieve true mastery even in any single one.

AI, meanwhile, has the potential not only to learn any software, but all of it, and to its full extent.

It can achieve mastery in individual applications but also logically use them in conjunction with each other, in ways most of us would probably not consider. And there's nothing stopping it from doing it at maximum speed permitted by current hardware, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

We simply cannot compete with that.

It's not a question of if but when, and that when isn't really distant either, since AI is, ultimately, just a piece of software itself.

There may be some doubt whether AI will ever think or feel quite like a human being, if it can form its own thoughts or take action on its own, but there is absolutely no doubt that it will be able to utilise perfect or near-perfect automation of software.

What place is for us in this new reality?

Replacing how with why

Since we can't compete with machines on skills it's quite likely that most of them will no longer be required for all but the select few humans e.g. those charged with maintaining the underlying systems, so at least someone understands how they work.

However, no matter how smart computers become, they are still mere servants helping us reach our goals (the topic of sentience is still highly speculative or even philosophical at this point, so I won't be considering Terminator-like scenarios here).

And, no matter the skill, the output is only as good as the instruction. So, before AI can answer your questions or provide appropriate solutions, it has to understand what it is expected to deliver.

That information will still have to come from us.

Much of human workforce, even today, is charged with performing quite mindless, repetitive tasks, adding a little bit of value like worker ants doing their part to keep the colony thriving.

Most of our time is spent on how to do what we're told – how to format a document, how to analyse data, how to design something – to produce the required output. Computers are already automating much of it but soon will make most of our involvement obsolete.

With machines capable of doing any job quickly and without complaint, our role will be reduced to supervisors, managers guiding them on the way. And every single one of us will have to either relay the reasons for why something is done to the machine, or contribute our own part to them.

This, of course, means that fewer people will be needed to do the same job. Even if a portion of the current workforce can be retained in these AI-management roles, not everybody can or will be.

On the other hand, however, the ubiquity of access to these AI tools will allow for creation of new companies by people who ordinarily wouldn't have mastered all of the specific, often technical, skills.

We may, therefore, see a rise in number of businesses, combined with a relative decrease in employment in office jobs in each single one of them.

However, not everybody is suited for a managerial role – whether working with humans or intelligent machines. Not everybody can have a vision of what needs to be achieved – so, what's going to happen to those people?

Revival of manual labour

Paradoxically, it seems that technological progress is about to complete a full circle. We've invented new things to make our manual jobs easier, until we reached a point where most employment is in intellectual, rather than physical, labour. But as thinking computers are about to start displacing us, many of our future jobs may be manual again.

The reason is very simple: it's much easier to digitalise a thought process, a software skill, a computer input, than it is to replicate the complexity, dexterity and agility of a human body.

And while progress is being made in that area as well, there are challenges that may not be overcome for many decades, if ever. Not because they are impossible but because it may not make economic sense to reinvent a physical human in an inherently imperfect machine form.

Upon reaching adulthood, a human can productively work for about 40 to 50 years, powered by about 3 meals per day. Ensuring the same level of reliability and energy efficiency in a robot is a struggle that may not be worth the effort and expense.

So, while many people will move up from repetitive office tasks to quasi-managerial roles in supervising and directing AI tools to produce creative outputs, those who are not fit for the job will don overalls and carry toolboxes around – often to keep those AI systems running.

There are millions of specialised robots in existence already, of course, but there's not one that comes anywhere near our physical adaptability. We can work in tight spaces, manipulating some of the tiniest and largest things. We are also able to reason, observe and respond to emerging problems in ways that machines won't be able to match for a very long time.

At the same time, keeping the multi-trillion dollar investments in hardware running data centers behind AI is going to require a very large workforce around the world.

And the labour requirements only cascade from there, since those facilities will have to be powered somehow, requiring investments in generation and transmission of electricity, as well as supporting industries of construction, mining and transport – jobs that are difficult to automate and will require considerable human involvement for the foreseeable future.

We still need plumbers, electricians, mechanics or technicians knowing which cables to plug in where – and then fix things when they go wrong. Robots are not coming for these jobs anytime soon.

This isn't some speculation about the future either, but an already observable trend as more of the young ditch university ambitions for a well-paying blue-collar employment. Automation of office work is only going to accelerate it.

Artificial intelligence is going to free us from office drudgery, leaving only the most creative humans in intellectual employment, to direct the thinking computers to perform what we want them to.

Meanwhile, those currently in support roles, will be forced back out to take on manual labour, that the demand for is about to increase.